Vulcan’s success in its product lines inspired imitators. One of the most significant of those came from its own distributor network—Conmaco. The relationship between the two companies was as complicated of a business as one could want, both together and apart.

Conmaco was started in 1910 as Contractors Machinery Company. Three years later Scott Myers, whose family came to become principals in the business, became associated with the company. In 1938 Vulcan and Conmaco signed their first distributor’s agreement in which the Kansas City, Missouri based business became Vulcan’s dealer in western Missouri and the entire state of Kansas.

While Vulcan’s future principal was off fighting World War II, the companies had their first falling out. In the spring of 1944 the Bureau of Yards and Docks sent out a bid to Conmaco for 254 drop hammers. Vulcan was only capable of delivering 112 of these by the end of the year, so Conmaco proposed that it produce the balance of the order itself. In good company tradition, Vulcan’s Secretary-Treasurer, Walter Daspit, flatly turned down Conmaco’s request. (William H. Warrington had set the precedent for this with Raymond before World War I.) On 20 May 1944, as the Allies celebrated taking the remains of the Monte Cassino monastery, Conmaco cancelled their distributor’s agreement with Vulcan, which Daspit accepted without any attempt at settlement.

The end of World War II also brought reconciliation between Vulcan and Conmaco. On 7 September 1945, five days after the Japanese surrendered to the Allies on the deck of the Missouri, Vulcan formally reinstated their Missouri-based dealer.

As the country’s economy shifted from wartime to peacetime, Conmaco pursued the capabilities it first explored during the war by either producing its own drop hammers or reselling those purchased at surplus. As early as 1949 Vulcan queried Conmaco on this matter. Nevertheless in the mid-1950’s Conmaco was generally Vulcan’s most important distributor. In September 1957 Vulcan and Conmaco (which had formally changed its name and moved to Kansas City, Kansas) signed a new distributor agreement.

Although Conmaco continued to be an important distributor and its territory expanded to other Midwestern states, the relationship progressively deteriorated during the first half of the 1960’s. Part of the problem was that the nature of the market was changing. Up until that time Vulcan had an extensive network of distributors which dealt in a wide variety of construction related products. Pile driving equipment is a specialized product in a specialized market, and “general equipment” distributors (even in some cases crane dealers, for whom pile driving equipment was a natural adjunct product) were losing interest in the product. Things were further complicated by the emergence of a rental market for the hammers. Vulcan’s entire marketing strategy was based on hammer sales; rentals (which made sense for infrequent users and joint ventures) cut into that. Conmaco responded to both of these trends by concentrating on the pile driving equipment (along with other related products such as winches and cranes) and developing a rental fleet. This last was not to Vulcan’s taste, although it was a market trend that ultimately Vulcan could do nothing about (and having as durable of a product as it had only accelerated the trend.)

Additionally, Conmaco continued to develop its own production capabilities of driving accessories, leaders and producing Vulcan hammer parts. This basically turned Conmaco into a competitor to Vulcan.

Things came to a head in January 1965 when Vulcan cancelled its distributor’s agreement with Conmaco. The situation was further complicated by the fact that Conmaco had hired Vulcan’s Vice President of Sales, Earle R. Evans, in February 1965. (Evans had been involved in the coming of Prince Alexandre de Rethy of Belgium to Palm Beach the previous month.) In spite of all of this the two companies remained in dialogue, so Vulcan continued to treat Conmaco as a distributor; however, there was no formal agreement until early the following year.

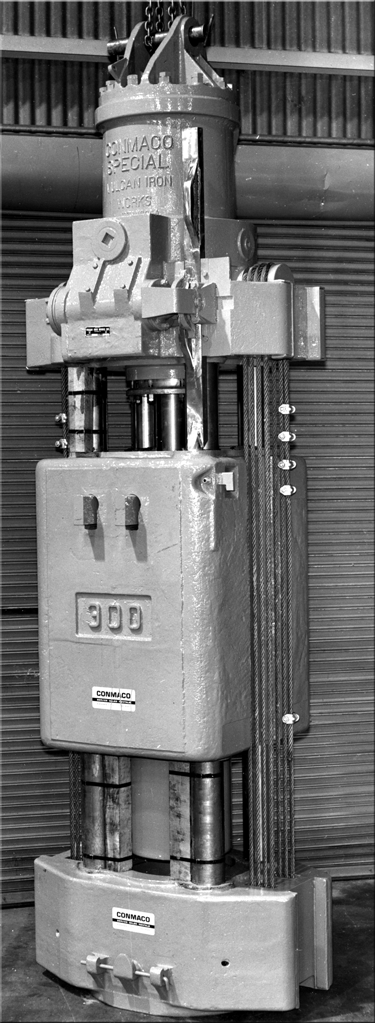

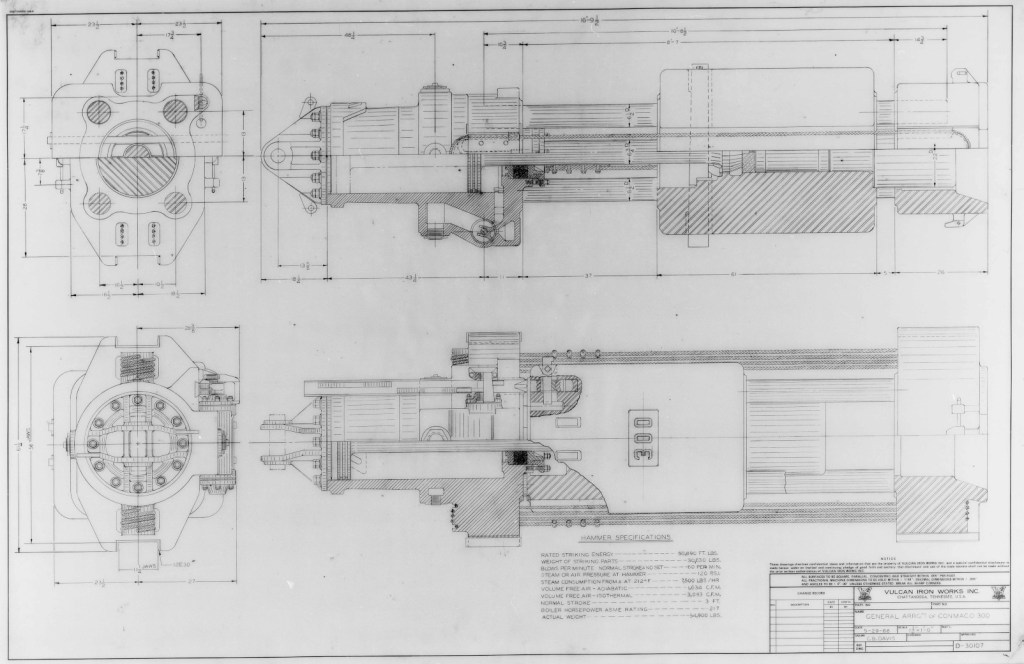

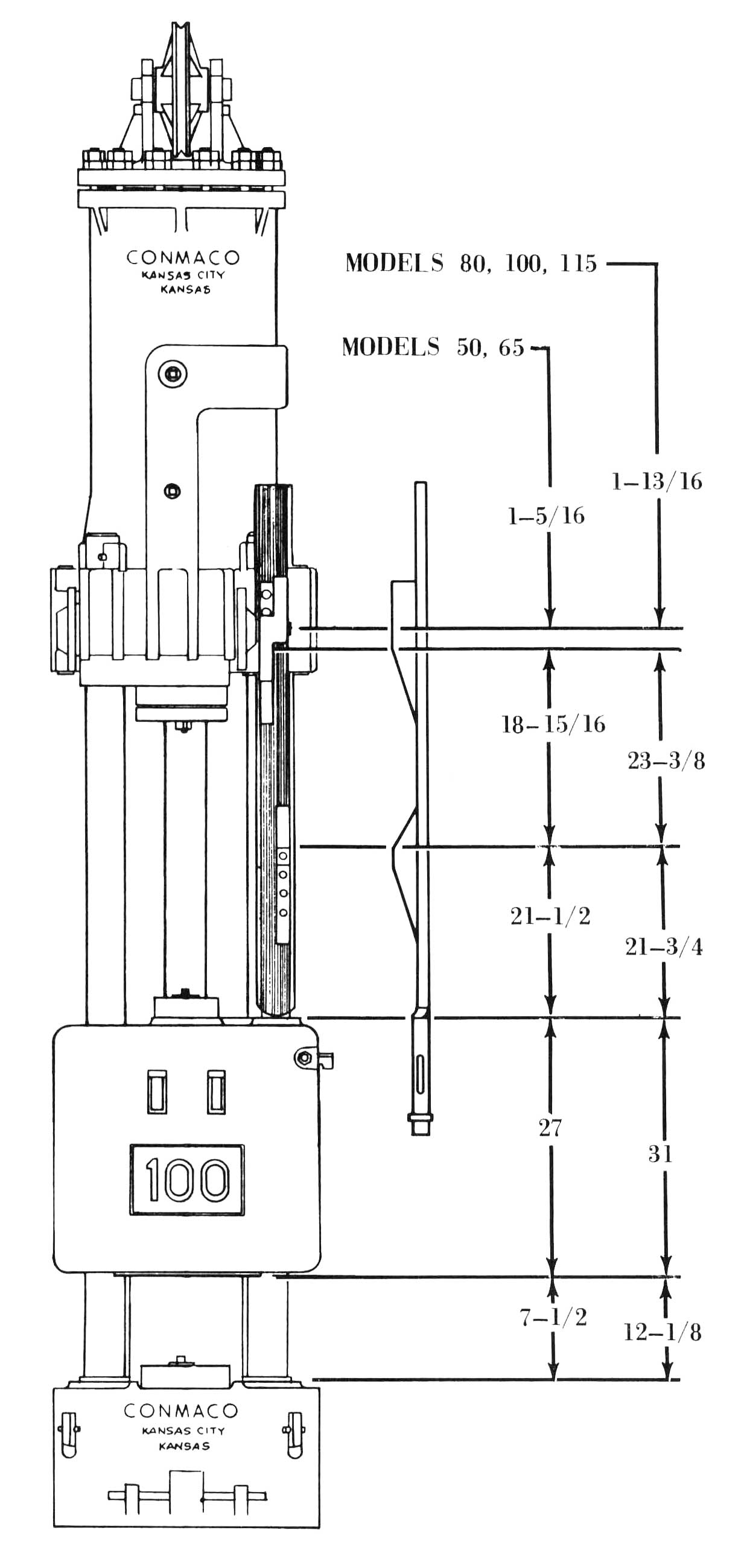

The two organisations spent the rest of the decade trying to maintain a relationship. At one point Conmaco even had their Chicago branch at Vulcan’s old facility at 327 North Bell. In 1967 Vulcan drew up and produced to Conmaco’s specifications the Conmaco 200 hammer, a counterpart to Vulcan’s 020. There were many detail changes, but the most significant was that the hammer was tied together with a cable wrap system designed by Dwayne Smith, Conmaco’s Equipment Manager.

The cable wrap system was a mixed business. One the one hand, the wrap system is labour-intensive and requires the hammer to have larger jaws (and thus require larger leaders) than the system that Raymond developed and Vulcan adopted for its own hammers. On the other hand the larger jaws made it simpler to accommodate larger piling, which is especially advantageous with hammers in the 300E5 range. Additionally the smaller Conmaco hammers sported cables of kind before their Vulcan counterparts did.

Vulcan went on to produce the Conmaco 140 and 160 hammers (counterparts to Vulcan’s 014 and 016 sizes.) But time was running out on the tempestuous relationship; the fundamental difficulties which led to the 1965 parting could not be resolved. In November 1971 Vulcan cancelled Conmaco as a Vulcan distributor because, as Vulcan’s President H.G. Warrington noted, “the general business objectives of Vulcan and Conmaco are basically inimical.”

In spite of the apparent finality of that cancellation, things weren’t quite over just yet. In August 1974 George Daniels of Conmaco’s Chicago branch had facilitated the test of Vulcan’s Decelflo muffler. Vulcan reinstated Conmaco’s Chicago branch only as a Vulcan dealer in October of that year, but it was short lived: within a year Vulcan once again cancelled the agreement, which proved to be the final one between the two organisations.

Conmaco went on to produce a line of Vulcan style air/steam hammers to cover most of the size range of the ones Vulcan had manufactured. During the 1970’s and 1980’s Conmaco was a competitor to Vulcan both onshore and offshore. Things flared up again in 1978 when Vulcan accused Conmaco of infringing upon its Vari-Cycle stroke control patent with Conmaco’s energy selector device. Conmaco responded with a cross-licensing proposal, but Vulcan, true to form, flatly refused its request.

Although Conmaco’s product line was developed as a competitor to Vulcan, the fact that the hammers that resulted were basically Vulcan style hammers are a testament to basic durability of both the design and the hammers. Additionally companies which service Vulcan hammers can also do the same for their Conmaco counterparts.

Additional information:

8 thoughts on “Conmaco”