In the earlier post Tapered Keys and Their Use In Vulcan Hammers we had a general discussion of tapered keys, the theory behind them and their application in Vulcan hammers. In this post we’ll look at one specific application–the Vulcan 560 Slide Bar Key–and see how Coulombic friction applies in this case of a self-locking (hopefully) application.

Tapered keys were ubiquitous in Vulcan products for many years–column keys, ram keys, valve stem keys, and slide bar keys. The slide bar keys generally ran through a slot in the slide bar. With the advent of nylon slide bars in the 1960’s, this virtually guaranteed (sooner or later) that the slide bar would split at the key slot. This led to the development of the slide bar gripper, first used on the 040 series of hammers, where the spherical bearing on the end of the bar was surrounded by a nylon gripper held in place by the key. These were an improvement and the subject of a U.S. Patent.

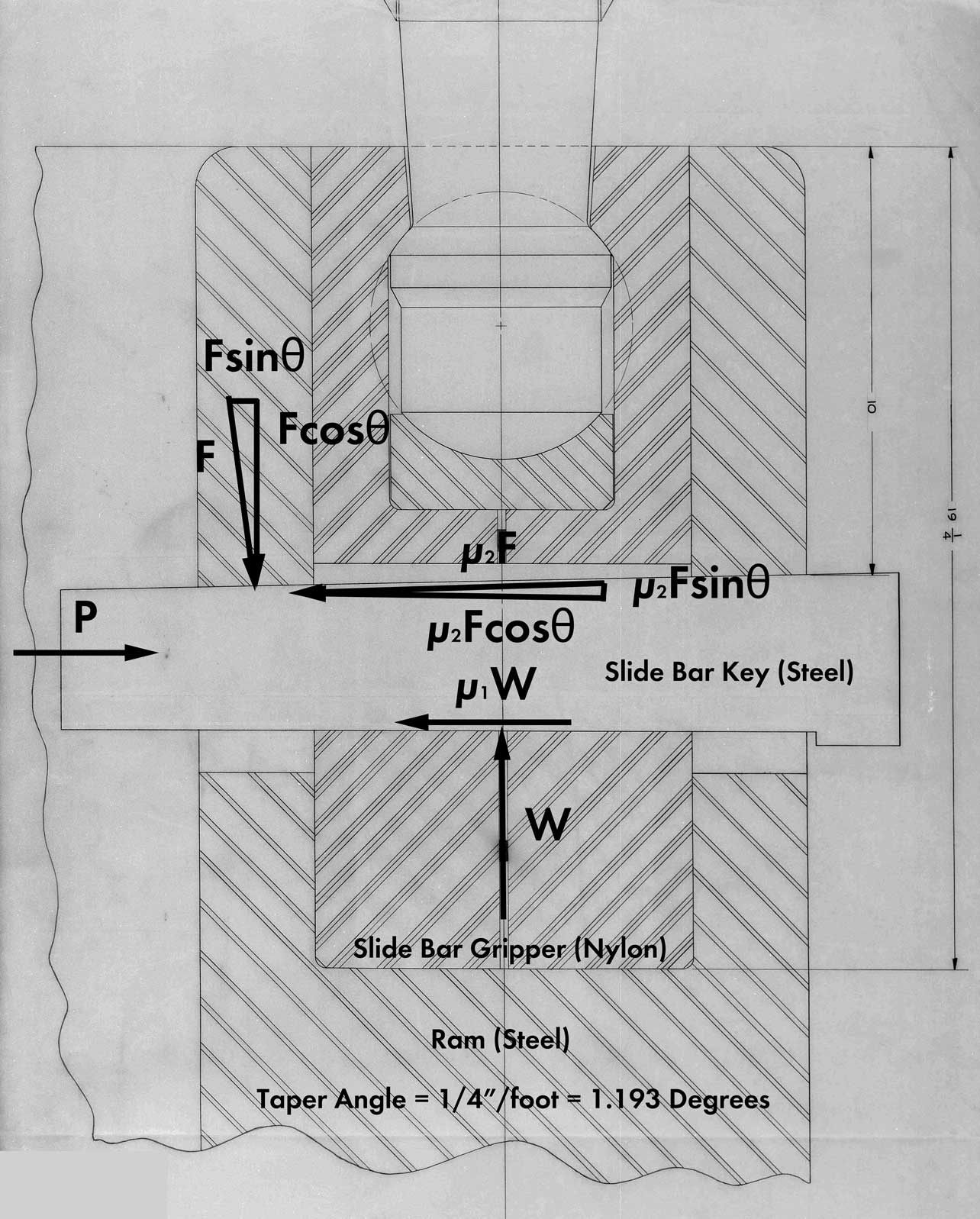

In any case we can apply the laws and methods of statics to analyse the forces on the slide bar key. We did so in Tapered Keys and Their Use In Vulcan Hammers but we’ll use a more contemporary approach to the statics. Additionally, since we have two different materials in play here (three if we considered a cast iron ram) we have two different coefficients of friction, which complicates the problem somewhat.

Consider the slide bar key setup above. The taper is at the top of the key and interfaces with the ram. The horizontal surface is at the bottom and interfaces with the slide bar gripper. The components and materials are shown. The force W at the bottom of the key acts in the y-direction upwards on the key. The force F at the top of the key acts normally to the top surface, which means that it’s at a slight angle from the y-direction. Both of these forces produce frictional forces by Coulombic theory, W in the x-direction and F parallel to the top surface. For all the F forces, it is necessary to break up both normal and frictional forces into their x- and y-axis components using force triangles.

The force P at the end is the force required to push/drive the key back out. If P is positive, the key is self-locking (which it should be.)

First consider the summation of forces in the x-direction:

(1)

Now the y-direction:

(2)

Solving Equation (2) for F,

(3)

Substituting that result back into Equation (1),

(4)

or

(5)

At this point we hit a snag: the force P to drive the key out is linearly dependent upon the force exerted on the key by the gripper W. In reality it’s the other way around: the force W depends upon how high the force to drive the key was in the first place. Usually Vulcan keys were hammered into place going in and driven out in like fashion.

In any case, let’s put some numbers of this. Assuming that there’s some oil or grease around the key, and

. The taper is

degrees. Substituting all that into Equation (5) yields

In reality the key is statically indeterminate; however, it shows the commonsense reality that, the harder the key is jacked/hammered in, the harder it is to get out. Thus, for example, for a desired force W of 500 lb, it would take 387 lb. of force to drive the key out.

In reality, as noted above, keys were hammered. Doing that creates plastic deformation in the key, the mating surface, or both. Under the punishing conditions of impact pile driving, this would lead to relaxation of the material and loosening of the keys. The keys were mechanically strong but required constant retightening, which could only go on for so long.

Vulcan looked for alternatives and one of them can be seen in the post Slide Bar Gripper. Another alternative was the cable tightened arrangement of the Vulcan 106: the “Switch-Hitter”. Raymond used a screw-tightened drawbar arrangement which got away from hammering the keys into place. For the column keys Vulcan replaced them with cable ties, as is evident on the 560 itself.

Nevertheless they provide an interesting application of Coulombic friction which served industrial products for many years and still has application today.

2 thoughts on “An Example of a Self-Locking Wedge: the Vulcan 560 Slide Bar Key”