This is a brief summary of the basic theory behind vibratory power. It goes back to Savinov and Luskin (the original summary of the development of the technology) and I’ve covered it repeatedly in my monographs.

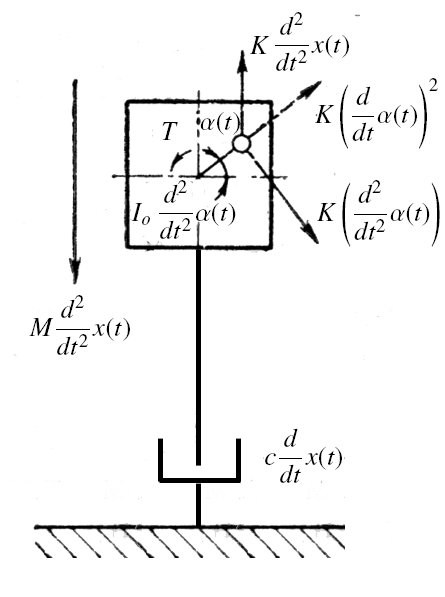

The basic model is shown above. It assumes that that soil acts as a velocity-dependent damper, which speaks to the liquefaction of the soil during driving but doesn’t really solve the problem of the resistance. The variables in this diagram are as follows:

- x(t) = movement of body, m

- t = time, seconds

- M = vibrating mass of driver and pile, kg

- K = eccentric moment, kg-m = mr

- m = eccentric mass, kg

- r = eccentric radius, m

- α(t) = angle of eccentrics

- Io = mass moment of inertia of eccentrics, kg-m2

- Since angular velocity ω (rad/sec) is assumed constant, α(t) and Io do not enter into our computations

- c = velocity dependent damping of soil, N-sec/m

To simplify later calculations, let us start by defining a dimensionless damping coefficient thus:

(1)

We can then state the equation of motion for the system as follows:

(2)

The steady state solution of this is

(3)

Differentiating this with respect to time to obtain the velocity,

(4)

The integral to obtain the energy expended during one cycle of the eccentrics is

(5)

We need to pause and consider the terms in the equation.

The Kω2 term is the dynamic force of the eccentrics. The sine term indicates the periodic nature of the force, which varies up and down as the eccentrics rotate (and cancel sideways as the eccentrics are in pairs.) The velocity term multiplied by the time increment is the displacement; energy is force times displacement.

Integrating Equation (5),

(6)

Differentiating Equation (6) with respect to the damping coefficient ζ,

(7)

Solving Equation (7) for the extreme values of damping,

(8)

This is important: it shows that the vibratory energy and power have a maximum theoretical value. What basically happens is that, as damping increases, the amplitude of the system decreases, and at a certain point the amplitude is lowered enough that the energy required by the system likewise decreases.

If we then substitute this result into Equation (5) and multiply it by the revolutions per second of the system, we obtain the power in watts, thus

(9)

There are two basic problems with this formulation.

The first is that, to maintain constant ω, it is necessary for the torque to continuously vary, as shown in the dimensionless diagram below.

It is unreasonable to assume that whatever motor is driving the eccentrics can match this perfectly, and thus is is necessary for the eccentrics to have some rotational inertia to keep the energy transfer going (infinite inertia in theory.)

The second is that the theory doesn’t take into consideration things such as losses in the vibratory system itself and non-viscous response of the soil. This has led to the modification of the “1/4” coefficient in Equation (9).

Both of these issues have been discussed in my monographs, which you can read below:

One thought on “The Basics of Vibratory Power Theory”