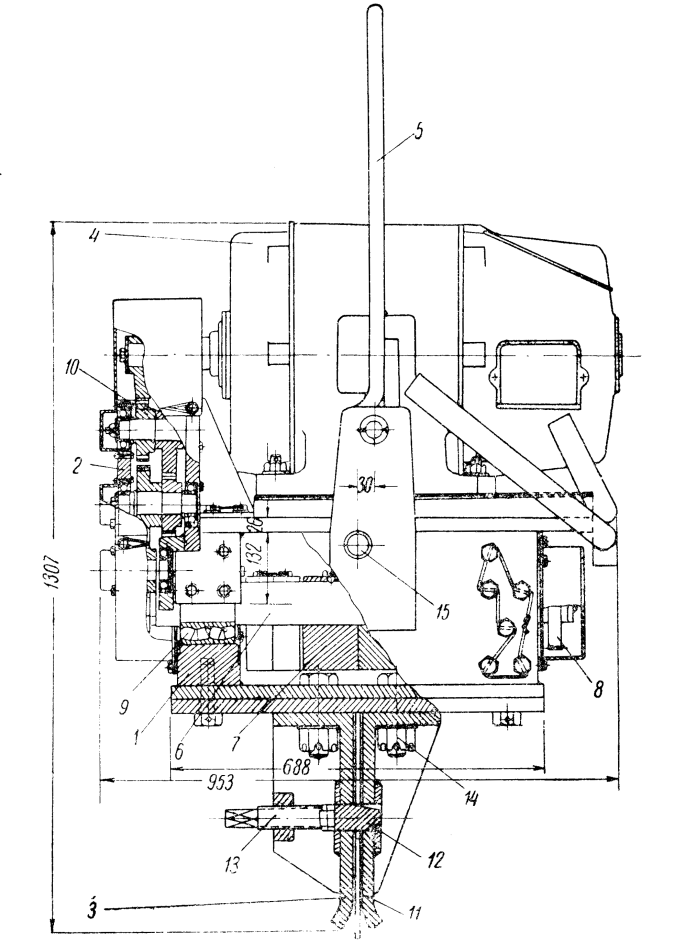

In the midst of posting The Vibration Method of Driving Piles and Its Use in Construction, it’s worth stopping and looking at the first successful vibratory driver: the BT-5, developed by D.D. Barkan and his associates and first used at the Gorky hydroelectric project in 1949. It was the first successful use of a vibratory driver on an actual civil engineering project.

In particular, let us compare this with another first (for Vulcan at least): the development of the 400, the first non-resonant, high frequency (by American standards) vibratory driver in the United States, which made its debut in Ft. Pierce, FL, in 1987.

Using Those Pesky Kilogram-Force Units, the specifications for the two machines are as follows:

| Parameters | BT-5 | 400 |

| Eccentric Moment, kg-cm | 350 | 230.4 |

| Rotational Speed, RPM | 2350 | 2400 |

| Dynamic Force, tons | 21.8 | 15.4 |

| Vibrator Weight, tons | 1.3 | 0.51 |

| Free-Hanging Amplitude of Vibrator Without a Pile, mm | 2.7 | 5.3 |

| Electric Motor Power, kW | 28 | 33.7 |

| Overall Dimensions in Plan, mm | 950 x 910 | 1651 x 914 |

| Height, mm | 1310 | 2134 |

It’s worth noting the following:

- The rotational speeds were virtually identical; ~2400 RPM was unusual for subsequent Soviet and contemporary American machines at the times the two vibrators were introduced.

- The 400 is a smaller machine in both eccentric moment and dynamic force, but not by that much. The 400 is also a lighter machine; the weight includes the static weight, which was not present on the BT-5.

- As was normally the case, the American machine had considerably more power at its disposal. This was a significant difference between American and Soviet vibrators, which came up during Vulcan’s discussions during its first visit to the USSR in 1988.

- The width of the American machine was considerably more than its Soviet counterpart; American machines were focused on getting between the sheets and didn’t worry so much about the width.

So how did both organisations end up producing machines that ran “against the grain” of orthodoxies of the time? The best place to start would be with the Soviets. There were two distinct theoretical threads in early Soviet development, as described in Existing Proposals for the Theory of Vibratory Pile Driving:

Work on the creation of such a theory was carried out in two directions. The first of them includes the works of D. D. Barkan [5], who, investigating the effect of vibrations on internal friction in sands, found that soil particles acquire mobility under this influence and the soil becomes similar to a viscous medium. D. D. Barkan proposed to characterize the mechanical properties of this medium by some coefficient of vibroviscosity, which depends on the physical and mechanical properties of the soil and on the acceleration of vibrations. The results of this study allowed D. D. Barkan to reduce the very complex issue of vibrational pile driving to the problem of immersing bodies in a viscous medium with a variable viscosity coefficient. Having considered this problem, D. D. Barkan obtained formulas for determining the soil resistance to the penetration of bodies, the average sinking speed, etc.

Yu. I. Neimark [37] and almost simultaneously with him I. I. Blekhman [11], M. Ya. Kushul and A.V. Shlyakhtin [26]. vibration penetration is possible without involving the hypothesis of liquefaction or any general change in the physical and mechanical properties of the soil under the influence of vibrations. Based on the usual ideas about the resistance of the soil environment to the penetration of a pile into it, the authors of these works assume that there is a so-called dry friction between the surface of the latter and the soil, and the relationship between the pressure of the lower end of the pile on the soil and its settlement is determined by one or another graph. With this formulation of the problem, it turned out to be possible to obtain formulas for calculating the maximum depth, average speed and time of immersion (or extraction) of the pile.

Existing Proposals for the Theory of Vibratory Pile Driving

In American usage, Neimark’s theory is closer to the “amplitude drives piling” concept. Barkan’s liquefaction concept, however, has a great deal of merit and is certainly taking place during vibratory pile driving. Since Barkan was the chief developer of the BT-5, it makes sense that he might want to try a low amplitude, high frequency vibrator which would result in a smaller machine.

It’s worth noting that Savinov and Luskin’s commentary on both of these theories is certainly relevant today:

Without dwelling on the later studies of S. A. Osmakov [38], A. S. Golovachev [22], O. Ya. Shekhter [66] and others, which are very similar in formulation to the works of Yu. I. Neimark, we note that none of the existing theoretical works gives a complete solution of the problem under consideration.

Existing Proposals for the Theory of Vibratory Pile Driving

For Vulcan’s part, its early researches into the vibratory driving physics showed that there was a possibility to getting around the “amplitude drives piling” conventional wisdom because of the obvious liquefaction. Vulcan would explore this in more detail in Warrington (1989.) European manufacturers had developed higher (2400 RPM) frequency, lower eccentric moment/amplitude machines, but their motivation was to vibrate piles around sensitive structures to prevent damage.

Vulcan’s rationale, however, was different, and driven by two realities:

- The advent of aluminium sheet piles, which were more sensitive to vibrations and clamping damage; and

- The need to produce a lighter vibrator than the competition at the time, namely the MKT V-2.

Vulcan succeeded on both counts and went on to produce other high frequency machines, including the 400A shown at the left.

For their part the initial application of the BT-5 was successful but had its issues:

The disadvantages of the BT-5 type vibrodriver are the unsuccessful selection of parameters at which the vibration amplitude is too low, and insufficient durability.

Vibrators of the Simplest Type

Vulcan went on to produce two larger high frequency units: the 1400 and the 2800. The former (shown at the right) was successful; the latter had, as was the case with the BT-5, durability issues, some of which related to the frequency, some of which did not.

The simplest way to sum up the utility of the high frequency units is to say that they are most effective with lighter piles with lower toe resistance, which means that, for both the flat sheeting the BT-5 drove and the aluminium (and other) sheeting the 400 and 400A drove, the configuration was satisfactory.

In spite of its limitations, D.D. Barkan’s “viscous” model became a favourite amongst equipment designers because of its simplicity, and is explored extensively in the references given below.

- Warrington, D. (1989) “Theory and Development of Vibratory Pile Driving Equipment.” Presented at the Twenty-First Annual Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, 1-4 May 1989.

- Development of a Parameter Selection Method for Vibratory Pile Driver Design with Hammer Suspension

- Reconstructing a Soviet-Era Plastic Model to Predict Vibratory Pile Driving Performance

- Two Papers on Vibratory and Impact-Vibration Hammers

2 thoughts on “D.D. Barkan’s BT-5 and the Vulcan 400”